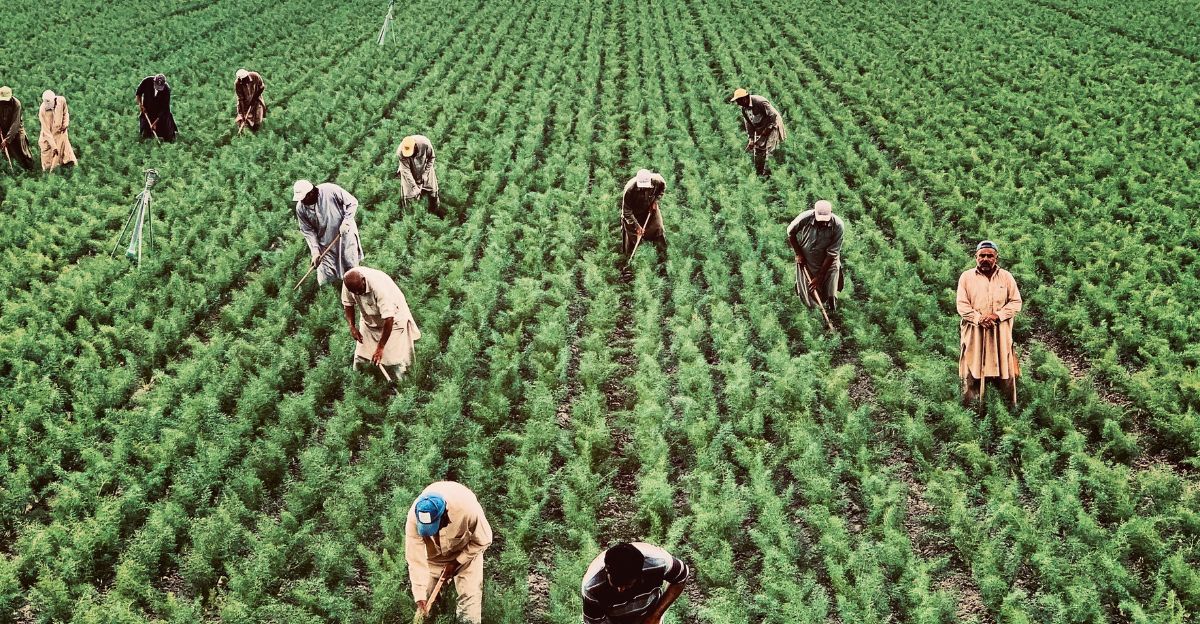

The farm labor shortage triggered by the mass deportations of undocumented workers has been all over social media, and the agricultural industry is grasping for options to get workers back in their fields. The proposal centers on tapping able-bodied adults enrolled in Medicaid to fill the field gaps.

Officials have cited a pool of 34 million Medicaid recipients as a potential workforce, sparking heated debate among policymakers, farmers, and civil rights advocates. Will this proposal work, or will it only overlook the greater problem?

The Policy Announcement

This announcement was made during a press conference in Washington, D.C., where Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said there would be “no amnesty” for undocumented migrant farmworkers, reaffirming the administration’s hardline stance on immigration enforcement. She insisted there is “no labor shortage in America,” suggesting that the Medicaid population represents an untapped pool that could staff agricultural jobs.

“When you think about it, there are 34 million able-bodied adults in our Medicaid program. There are plenty of workers in America, but we just have to make sure we are not compromising today, especially in the context of everything we are thinking about right now,” Rollins said. “So, no amnesty under any circumstances, mass deportations continue, but in a strategic and intentional way, as we move our workforce towards more automation and towards a 100% American workforce.”

The Numbers Behind the Plan

Often, reality is more challenging than statistics make it out to be. Federal figures show there are about 29.2 million working-age adults on Medicaid, not 34 million as stated by officials. Nearly two-thirds, around 18.7 million, are already employed, full-time or part-time, or are engaged in school or caregiving responsibilities. Only a small fraction, estimated at around 2 to 5 million, are able-bodied adults not working for reasons other than disability, caregiving, or education.

Meanwhile, the agricultural sector faces a severe labor shortage, with up to 70% of farm workers having stopped reporting to work in some regions following immigration enforcement actions.

Critics’ Reaction and Frustration

Many agricultural leaders and growers have openly dismissed the idea as unrealistic and out of touch with the realities of modern farming. Helen McGrath, a citrus and avocado grower in California, described the announcement as “insulting,” noting that most farmers “either laughed out loud or were just deflated by those comments.”

“They are literally talking about rounding up the poorest Americans—disproportionately Black and brown—and telling them to replace deported immigrants in the fields. That’s not a jobs program. That’s forced labor,” said a policy researcher who reviewed Rollins’ comments.

A Look Into the Past

The idea of replacing immigrant farm labor with domestic workers is not new, and history is littered with failed attempts. In the 1990s, the U.S. government launched “Welfare to Work” initiatives as part of sweeping welfare reform, aiming to move able-bodied adults from public assistance into the workforce, including agricultural jobs.

The reality fell far short of policymakers’ hopes. Most welfare recipients lacked the physical stamina, agricultural skills, or willingness to endure the harsh conditions of farm work. Many recipients cited the grueling nature of the work, lack of childcare, transportation barriers, and low pay as insurmountable obstacles. Needless to say, the program, like many others, didn’t go much further.

Automation: A False Promise?

While automation is often seen as the ultimate solution to America’s farm labor crisis, reality might not be as simple. Advanced technologies have indeed improved efficiency and reduced some input costs for large-scale operations, but the promise of automation might not be realistic. Many of the most labor-intensive tasks, especially in fruit and vegetable production, still require dexterity, judgment, and adaptability that machines don’t have.

“As far as automation,” a San Joaquin Valley grower said, “there is no automation. If I could replace those 20 people with machines,” he said, “I would.” But tree fruit are extremely delicate. “If you look at an apricot the wrong way, it will turn brown,” he joked.

Legal and Ethical Concerns

Legally, critics argue that compelling low-income Americans to work in agriculture as a condition for retaining health coverage may violate constitutional protections against involuntary servitude and run afoul of labor and disability rights statutes. Federal law has never required Medicaid recipients to accept specific jobs, and past attempts to tie health benefits to employment have faced successful court challenges.

A civil rights advocate stated, “This is not immigration policy. This is an attempt to resurrect slavery in America under a different name.” Ethically, civil rights advocates warn that the policy targets vulnerable populations by turning a health safety net into a labor registry, raising concerns about coercion, discrimination, and the erosion of basic human dignity.

Medicaid Work Requirements

To maintain Medicaid eligibility, these individuals must complete at least 80 hours per month of work, job training, education, or approved community service activities. The law includes numerous exemptions for people in different situations. States must verify compliance at application and at least every six months, though some may opt for more frequent checks.

Implementation is set to begin nationwide by the end of 2026, with states permitted to apply for waivers to start earlier. While supporters argue these requirements will promote employment and reduce government spending, critics warn that millions could lose coverage due to administrative hurdles or unstable work hours, especially those already working in low-wage or seasonal jobs. “They are taking a program that exists to guarantee health care and twisting it into a list of people they believe should be forced into field labor,” said a D.C. advocate.

Impact on Food Security

According to experts, mass deportations and the loss of experienced immigrant labor will most likely lead to food shortages and higher prices. As undocumented workers are removed, farms are left without the skilled labor needed to plant, tend, and harvest crops. This has already led to unharvested produce, supply chain disruptions, and a 20% drop in some crop harvests, with direct consequences for food availability and affordability.

Experts warn that these trends undermine the stability of the domestic food supply, making the U.S. more vulnerable to global supply shocks and reducing the nation’s ability to ensure access to healthy, affordable food for all.

An Uncertain Future

The future of American farming and health care is unclear. With new laws, fewer immigrant workers, and changes to Medicaid, no one knows exactly what will happen next. Farmers worry about finding enough people to pick crops, and many families are concerned about losing health coverage or paying more for food. Some hope that new technology or different policies will help, but there are no easy answers.