A paradoxical tipping point has been reached by the American fast-food industry, employees who prepare and serve meals on a daily basis are unable to afford to eat them themselves. According to recent studies, the average American worker needs only roughly 21 minutes to eat one meal at work, whereas fast-food employees must work for almost an hour to afford it. The fast food affordability crisis highlights the vulnerability of America’s low-wage labor model and the widening gap between corporate profits and worker well-being. It is a microcosm of larger economic dysfunction.

This phenomenon demonstrates how the fast-food industry, which was formerly a representation of easily accessible jobs and reasonably priced dining, now mirrors structural economic disparities. Addressing more general social and economic justice concerns in America requires an understanding of this fundamental contradiction.

A Historical Viewpoint

Teenagers used to view working in fast food as a stepping stone or a side gig to supplement their income. But in the last thirty years, it has become the main source of income for millions of adults who support their families. Despite this change, living expenses, including the price of fast food itself, have increased while wages have remained stagnant. This reality led to the creation of the “Fight for $15” movement in 2012, which called for fast-food workers to have union rights and a livable wage.

However, as workers’ financial insecurity increases and inflation surpasses wage increases, this model is no longer viable. A labor force that is more dependent on government assistance and susceptible to economic shocks is a result of the historical disregard for worker welfare in favor of shareholder returns.

The Paradox of Wage-Meal

The average flagship meal costs $11.56 in 2025, while the average fast-food worker makes around $15 per hour. This implies that a worker needs to put in 46 minutes of work to pay for one meal, as opposed to the typical American worker’s 21 minutes. Even a $20.83 hourly wage still requires 34 minutes of work per meal in high-cost cities like San Jose, whereas non-fast-food workers in the same city only require 12 minutes. This wage-meal disparity is a clear sign of how the economics of the sector are essentially out of step with the demands of the workforce.

Regional variations in the cost of living compound the paradox, making it even more difficult for workers in pricey urban areas. Furthermore, fast-food chains’ pricing policies, which frequently put profit margins and shareholder dividends first, create an environment in which workers’ pay does not adequately compensate them for the value of their labor or the true cost of living.

The Gap in Living Wages

When you factor in total living expenses, the situation becomes even worse. Fast-food employees in the ten American cities with the biggest wage gaps make more than 42% less than a living wage and would have to put in more than 70 hours a week just to make ends meet. Workers in the city with the smallest gap, Fresno, California, still have to work more than fifty hours a week just to make ends meet.

Disadvantage is further cemented by the long hours needed to meet basic needs, which also lead to burnout and poor health outcomes. The fact that this disparity still exists in spite of productivity increases and economic expansion indicates serious structural problems with labor markets and wage-setting processes, underscoring the pressing need for legislative changes to guarantee that wages are in line with living standards.

Food Workers’ Food Insecurity

Ironically, compared to workers in other industries, food service employees are 2.5 times more likely to experience food insecurity. The median hourly wage is still below $9 for many, and 87% of people do not have health benefits, and nearly 11.3% depend on SNAP benefits.

These workers’ food insecurity has wider societal repercussions, such as higher healthcare expenses, decreased productivity, and a rise in social inequality. These issues are made worse by the absence of benefits like healthcare, which deprives employees of safety nets. This scenario raises moral questions regarding social justice and corporate responsibility and calls into question the viability of an industry model that relies on low-wage labor supported by public welfare programs.

Poverty and Homelessness

In California, fast-food workers account for 6% of the state’s homeless population and an astounding 11% of all homeless workers. Their ability to find stable housing is hampered by low pay, part-time work, and a high employee turnover rate.

Instability in housing has a negative impact on employees’ physical and mental well-being as well as their capacity to hold down steady work, which feeds the poverty cycle. The high rate of homelessness among fast-food employees is a clear sign of structural economic failure and a wake-up call for lawmakers to fully address worker protections, wage reforms, and affordable housing.

The Dilemma of Automation

Automation can reduce the cost of producing fast food, but it also runs the risk of eliminating low-wage jobs, which would further worsen millions of people’s financial insecurity. The future of work and the social contract between employers and employees are other issues that automation brings up. Although technology can increase the speed and consistency of services, it frequently does so at the expense of livelihoods and human dignity.

Given how difficult it is for displaced workers to find new jobs in an already difficult labor market, the change could increase economic inequality. Leaders in the industry and policymakers must think about how to strike a balance between social responsibility and technological advancement, including retraining initiatives and wage protections.

Inflation of Prices and Shrinkage

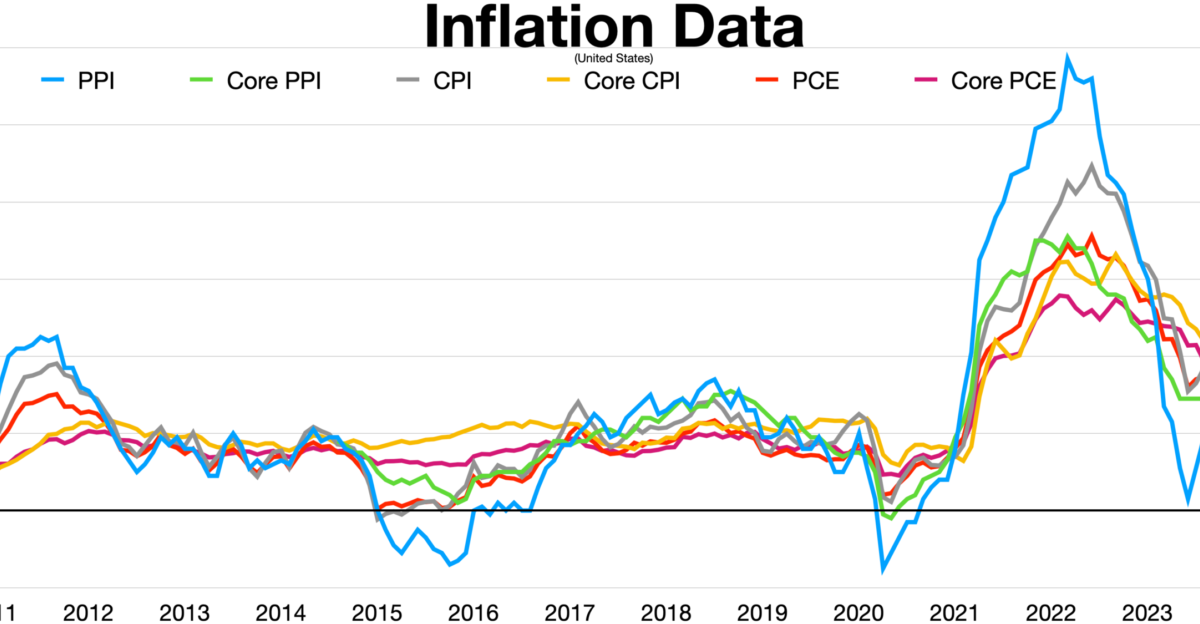

Fast-food prices increased by up to 28% between 2019 and 2023, surpassing both wage growth and general inflation. Chains make fast food less affordable for everyone, particularly for those who work behind the counter, by passing on higher labor and commodity costs to consumers.

In addition to corporate strategies to preserve profit margins, this trend reflects broader economic pressures such as rising commodity prices and supply chain disruptions. The combined result is a fast-food market that is becoming more and more unaffordable for low-income workers and consumers, casting doubt on the industry’s long-term sustainability and undermining its reputation as an inexpensive food source.

The Toll on Social and Psychological Aspects

Employees who are unable to pay for the food they serve suffer significant psychological effects. Anxiety, despair, and low self-esteem are exacerbated by ongoing financial strain, food insecurity, and housing instability. Few people in the industry have collective bargaining power to improve conditions because of the low unionization rate of just 1.4%. In the meantime, calls for systemic change and labor unrest are being fueled by the public’s growing awareness of these injustices.

In order to empower employees and restore dignity, addressing these psychological effects calls for comprehensive strategies that include equitable pay, benefits, mental health assistance, and more robust labor representation.

How did America fare?

The fast-food industry in America, which was founded on the promise of opportunity but now keeps millions of people in poverty and hunger, is a prime example of systemic failure. The disparity between executive compensation, corporate profits, and the suffering of frontline workers is not coincidental; rather, it is the consequence of intentional policy decisions, labor models, and economic priorities.

The crisis will worsen and threaten not only workers but also the social fabric of the country if decisive action is not taken to realign wages, prices, and corporate accountability. This circumstance is indicative of larger patterns in American capitalism, where deregulation and wealth concentration have put profits ahead of people.