You’re standing in line at Waffle House, thinking twice about your usual breakfast order. Maybe it’s the All-Star Special or the Two-Egg Breakfast, but lately, it’s been harder to justify the cost. That quiet 50-cent egg surcharge pushed already pricey plates just out of reach.

Now, Waffle House says that the fee is finally off the menu. Waffle House officially announced the change last week, even though it quietly removed the charge a month earlier. This isn’t just about saving money. It’s a sign that food inflation may finally be easing.

Let’s take a closer look at what caused the egg crisis, how restaurants responded, and what it means going forward.

Waffle House Quietly Dropped the Egg Fee

Waffle House made it official last week on July 1: the egg surcharge was gone. But behind the scenes, the chain had already removed the charge back on June 2. The Georgia-based company, which serves about 272 million eggs every year at over 2,000 locations, introduced the 50-cent per-egg fee in February when prices spiked.

Now that markets have settled, they felt confident removing it. This careful move shows how temporary price hikes can work when done right. The company acted fast when prices rose, then rolled back charges as soon as things got better. That’s how you keep trust in tough times.

Bird Flu Was the Main Cause

The egg shortage didn’t come from supply chain delays or bad weather. It came from a deadly outbreak of bird flu that started in 2022 and kept spreading. Over 169 million birds have been affected since then, including more than 30.6 million in 2025 alone. The H5N1 virus hit egg-laying hens hard, especially those in cage-free farms, which supply states like California.

Once a farm found infected birds, it had to kill the entire flock to stop the spread. These sudden losses caused serious shortages, especially during holidays when demand for eggs is already high. That pressure drove prices up fast.

Egg Prices Reached Record Highs

At the peak of the crisis, egg prices were shocking. In March, wholesale eggs hit $8.17 per dozen. Retail prices weren’t far behind, reaching $6.23 per dozen that same month. That’s nearly six times more than the usual average of $1.40.

For restaurants, the hit was huge. A case of eggs that used to cost $30 or $35 suddenly cost $120 or more. There was no way to absorb that kind of jump without making changes. That’s when places like Waffle House decided to charge extra for eggs, just to stay afloat. And they weren’t the only ones.

Other Diners Took Action Too

Waffle House wasn’t the only one. Denny’s also added egg surcharges in February and removed them by May. Others used creative pricing or updated menus to deal with rising costs. Some smaller diners added small fees per egg, while others hid the costs in new item prices.

Denny’s limited its surcharges to places hit hardest by the shortage. Cracker Barrel, on the other hand, avoided adding fees and used it to stand out. They even offered extra loyalty points to win over customers. These different strategies show how every restaurant had to make quick decisions in a time of crisis.

Prices Dropped As Bird Flu Slowed

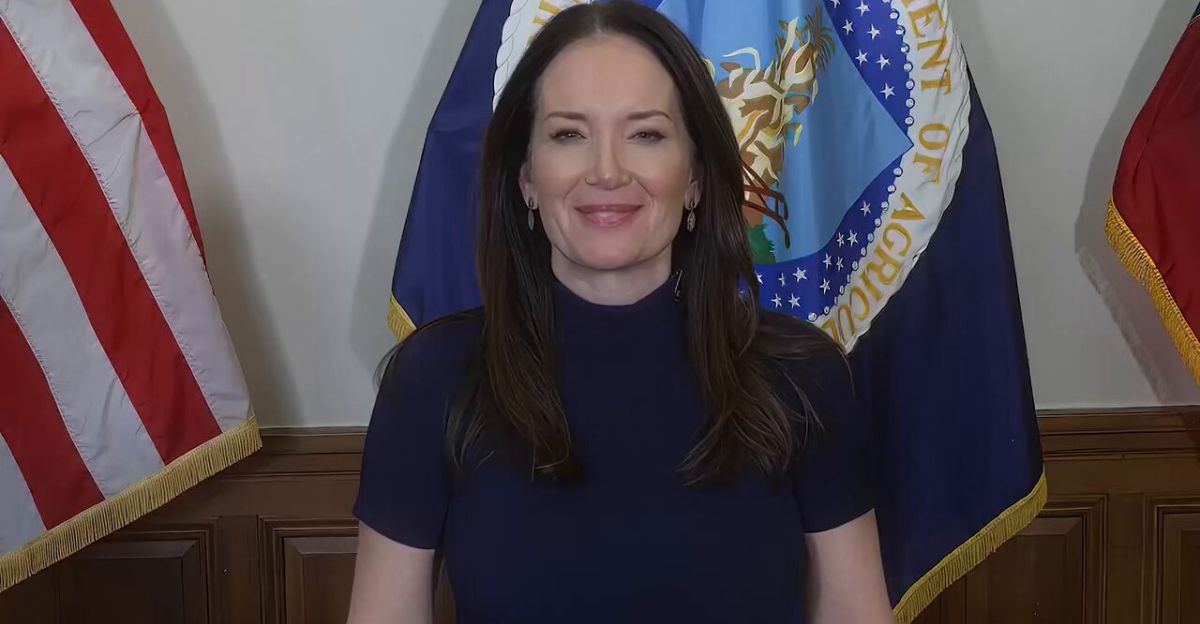

By spring, things started looking up. Wholesale egg prices dropped by 64% from their peak. Retail prices fell by 27%. U.S. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said families were finally seeing relief in the April Consumer Price Index. The drop in prices came with fewer bird flu outbreaks and more stable supply.

The USDA stepped in with help, offering free safety checks and paying part of the cost for farms to improve defenses. The U.S. also brought in over 26 million dozen eggs from countries like Brazil, Mexico, and South Korea. The worst of the egg crisis was over.

Customers and Workers Reacted Positively

When Waffle House made the announcement, the response was immediate. People went online to share their thanks and appreciation. Some said it was nice to see a company be upfront during tough times.

Industry experts also praised Waffle House for doing it right: being clear about why the fee existed and removing it as soon as possible. It wasn’t just about saving 50 cents. It was about being honest. That kind of communication builds long-term loyalty. When companies show they care during hard times, customers remember. And that goodwill is something you can’t fake or buy.

Not All Prices Are Going Down

While egg surcharges are gone, many food prices remain high. Restaurant costs are shaped by a lot of things, not just eggs. Labor shortages, fuel costs, rent, and other ingredients all affect the bottom line. Some Waffle House customers online said other items are still more expensive than before.

Even though the egg fee is gone, a full return to pre-inflation prices may not happen anytime soon. Inflation may be slowing, but it hasn’t disappeared. That means food businesses are still trying to figure out how to keep prices fair while staying afloat. There’s still work to do.

More Trouble Could Be Coming This Fall

Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins warned that the fight isn’t over. Fall is a risky time, because migrating wild birds can spread bird flu again. The USDA is watching closely, and they say price swings could return later in 2025. Warmer temperatures and unfrozen lakes are causing birds to stay in northern areas longer than before. This could change how and when bird flu spreads.

Experts say to keep an eye on egg prices in stores and restaurants. If new outbreaks happen, shortages could come back. While things are better now, the egg market may face more ups and downs ahead.

What This Says About Food and Trust

Waffle House removing its surcharge wasn’t just about eggs. It showed how a company can handle a crisis without losing customer trust. They charged when they had to, explained why, then removed the fee once prices fell. That kind of honesty matters. It sets an example for how to deal with future food shocks.

Prices may go up again, especially in fall, but what customers want most is clear communication. The next time you order breakfast without doing math in your head, remember what it took to get there. Food costs are changing fast, but trust should stay constant.